Pop Mart is upping the ante in its attempt to crack down on “counterfeit” Labubu toys allegedly being sold in 7-Eleven outposts. In a newly-filed amended complaint, the Chinese toy giant lodges claims against an array of new defendants and sets out a sweeping factual record to back up its case that the American convenience chain and at least 10 franchisees – from those in Laguna Beach to Los Angeles – are on the hook for selling so-called “Lafufus.”

What started as a something of a straightforward infringement lawsuit against 7-Eleven is evolving into a broader fight with a growing defendant list and an expanded factual record. At stake is not only the integrity of Pop Mart’s buzzy Labubu character – now a “global viral phenomenon” – but also the broader question of how far rights-holders can go in their efforts to hold parent companies like 7-Eleven responsible for the actions of their franchisees.

The Background in Brief: Pop Mart filed suit against 7-Eleven, Inc. and several franchise operators in the Central District of California in July, accusing them of selling counterfeit Pop Mart products in violation of federal trademark, copyright, and unfair competition laws. In its complaint, Pop Mart pointed to social media posts and in-store sales of allegedly infringing Labubu toys at multiple 7-Eleven-branded locations, alleging that 7-Eleven has the “right and ability to control,” including through franchise agreements and inventory systems.

Pop Mart Ups the Ante

Setting the stage in the September 26 amended complaint, Pop Mart details its Labubu-specific IP portfolio, the sky-rocketing demand for the character, and the global reach of its business. “In addition to innovative toy design,” Pop Mart says that it is also “an innovator in toy presentation, offering its products in a variety of fun and exciting ways, including ‘blind box’ presentation in stores, robotic vending machines, and official online channels.”

In terms of its IP, Pop Mart asserts that has “registered federal trademark rights in the POP MART, LABUBU, and THE MONSTERS marks, and common law trademark rights in the marks; unregistered federal trade dress rights in the design and appearance of the LABUBU products; and U.S. copyright registrations protecting product and packaging designs in the LABUBU Blind Box Series.” And with such rights in mind, Pop Mart sets out claims of direct federal trademark counterfeiting and trademark infringement, trade dress infringement, and copyright infringement as it did in its initial complaint.

In a departure from its initial complaint, Pop Mart breaks out vicarious and contributory liability theories as separate causes of action for each infringement claim this time around, angling to reach every potential defendant in the chain – from franchisees that directly sold the toys to 7-Eleven, Inc., itself – and avoid dismissal. After all, 7-Eleven argued in a motion to dismiss early this month that Pop Mart “mischaracterize[d]” the nature of the 7-Eleven franchise system in its initial complaint and failed to allege any infringing conduct by 7-Eleven corporate stores, as opposed to individual franchise entities.

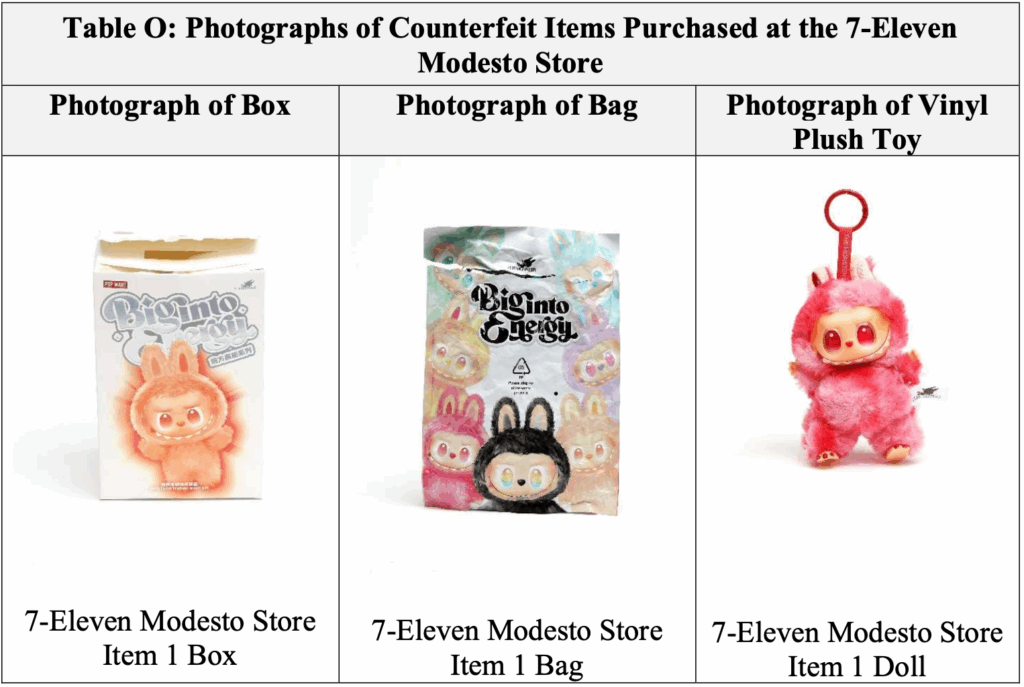

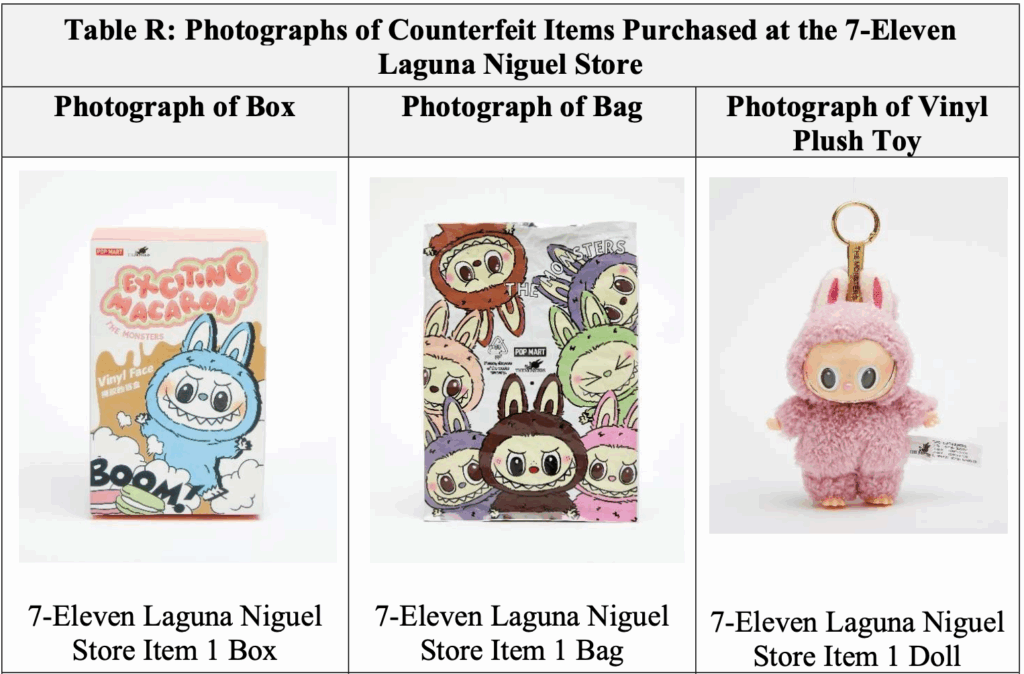

Beyond expanding the defendant list, Pop Mart’s amended complaint also provides a far more detailed factual record than its initial filing. Most notably, the amended complaint lays out store-by-store evidence of alleged infringement, as well as TikTok posts in which consumers show off Labubu purchases from 7-Eleven, often questioning their authenticity; side-by-side comparisons of genuine Pop Mart products and alleged counterfeit versions, including packaging and product design; and examples of consumer confusion, such as posts where buyers assume that the presence of the Pop Mart name on packaging means the product is the real thing.

Parent vs. Franchisee Liability

While the amended complaint dramatically expands Pop Mart’s claims with regards to the individual franchises at play, the company may face challenges in proving vicarious liability against 7-Eleven, Inc. as the corporate parent. U.S. courts generally distinguish between franchisors and franchisees, with liability for day-to-day sales often falling on the individual operators unless the parent company exerts substantial control over the infringing conduct.

To hold 7-Eleven directly liable, Pop Mart will need to show that it is not merely a licensor of the franchise system but was actively involved in, or willfully blind to, the sale of counterfeit goods. Without such evidence, claims against the franchisees and their principals – who directly purchased, stocked, and sold the products – may prove more straightforward.

On the other hand, Pop Mart’s decision to plead contributory and vicarious liability theories for nearly every IP claim reflects a strategic effort to preserve arguments at every level of the distribution chain. If it can demonstrate that 7-Eleven either encouraged or failed to stop widespread counterfeit sales despite having the ability to do so, the company could potentially extend liability beyond individual stores.

The case is Pop Mart Americas Inc. et al. v. 7‑Eleven, Inc. et al., 2:25‑cv‑06555 (C.D. Cal.).